Philosophy of care

for weight concerns.

Non-Diet Nutrition Counseling

All bodies are worthy bodies.

Non-diet nutrition is a weight-inclusive approach with a focus on health gain rather than pursuing weight loss.

This approach takes the stress from food and releases you from diet fixation and guilt.

We live in a world where diet culture and body-size focus has become the norm. We are bombarded by nutrition ‘noise’ every day.

In sessions, we create space to dial down that noise. We explore how weight stigma and diet culture have impacted your relationship with food, movement, your body image and health. You are supported to make sense of what is no longer serving you. You are supported to re-connect with your inner knowing when it comes to nourishing and moving your body.

It is in this space that sustainable, enjoyable, health promoting behaviours begin to take root (if you want them. There is no judgement if you don’t).

It is in this space that food takes its rightful place (spoiler alert - a very small part of who you are).

Working with Wellbe - the nuts and bolts

My approach is informed by the Non-Diet Approach (Fiona Willer PhD, APD), Intuitive Eating (Evelyn Tribole RD, Elyse Resch RD), the Plate-by-Plate Approach (Wendy Sterling RD and Casey Crosbie RD), and Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).

Mind-body self-care

Mindfulness, mindful eating and mindful movement can powerfully enhance inner connection, and this spins out into other areas of our life, such as relationship with food and eating. We can weave these practices into your care as much or as little as is helpful for you (they might not be your bag or they may not be suitable for you right now - together we figure out what is best care of you, you are in the driving seat).

Practice foundations

-

All bodies are worthy bodies

-

You are the expert of you

-

Body connection rather than body control

-

Wellbeing, rather than pursuit of weight loss

Why ‘non-diet’?

Weight is not a behaviour

If your wish is to pursue health (and there should be no moral judgement if it isn’t!!), research shows that self-compassion, stress management, sleep, flexible eating based on satisfaction, and movement for enjoyment sake ARE THE WAY TO GO.

Crucially, the secret ingredient is the intention behind behaviours - acting from a wish to care for your whole self, flaws and unwanted parts and all, rather than the intention to fix yourself.

Dieting doesn’t work for most people long term

Dieting to control body weight doesn’t work long term for most people. It is not personal failure, lack or willpower or a knowledge issue. It is complex biological systems that have evolved from millennia of surviving famine. You haven’t failed, the diets have failed you.

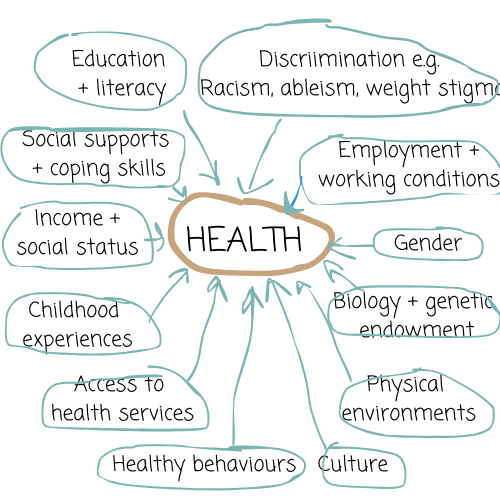

Health is complex & deeply personal

If you are higher weight you may have experienced your health being whittled down to the number on a weighing scales. The reality is that health and well-being are complicated. And very personal. It’s fair to say health is a resource that allows us to live fulfilling lives whatever that might mean to each of us. Health includes physical health, but also relationship (with ourselves and with others), community, emotional well-being, mental health, spirituality, economic well-being, vocational pursuits, hobbies, laughter, and many other things.

What does health mean to you?

The ‘pot’ of health

The relationship between higher weight and health is not straightforward. Like a recipe, there are many other ingredients in the pot that is our health - things that shape our behaviours, our stress loads, and ultimately our physical and mental well-being.

“People’s health cannot be disentangled from the circumstances of their lives” (Calogero 2018). Weight-inclusive care advocates for fair accessible healthcare for all - this would improve the health of the nation more powerfully than individual behaviour changes ever can.

Why does it matter?

“….evidence shows that behaviour does not necessarily control a persons body weight, and body weight does not always reflect health”

— Orr et al., 2023. Towards Size Inclusive Health Promotion. Insights and lessons for health promotion professionals.

But, we have had decades of messaging that we should control our body weight and that higher weight is inherently bad for health.

We may have learnt from a young age to ignore, over-ride or control our body.

…whether that was to do with body shape, fitness or performance. This spins into how we relate to food, eating and movement and ultimately how we relate to ourselves.

Illness, injury or aging can also bring us into a sense of body mistrust when there are changes to our body, or unpredictable or chronic symptoms.

We might spend our vital energy on conquering our body, or else shielding from a weight-focused society and healthcare system.

How has this impacted you?

…perhaps you have had to deal with the distress of weight-stigma - in healthcare, in public places, in your home.

…perhaps how you see yourself in the world has been dominated by how you view your body-size.

…perhaps you have put joy in your life on hold until you finally ‘get on top of the weight’.

…perhaps physical activity has become penance for what you eat or plan to eat.

You are not alone.

Reclaim your relationship with health and wellness.

Further reading for the readers…

-

You may have noticed an absence of the ‘O’ words in my writing. “Obesity” and “Overweight”.

These words are considered neutral descriptors in healthcare.

I have distanced myself from these words as they are problematic and stigmatising in everyday life.

Healthcare has tried to address this by introducing ‘person first’ language as it believes this to be more respectful (e.g. referring to ‘a person with “obesity”’ and “living with obesity””). This is fraught with tension in other areas where person-first language has been introduced). If you are interested Regan Chastain has written on this topic here.

The term ‘fat’ it is a term accepted within the size acceptance and fat acceptance communities. The word has been reclaimed as a neutral descriptor and to normalise the existence of fat bodies. However for many this word is associated with difficult memories and suffering and it does not feel neutral.

I have not had to endure weight stigma or weight based discrimination because of my body size. I don’t assume to know what it is like to walk in someone else’s shoes.

In my writing I tend to use words like ‘higher weight’ or ‘larger bodied’, but these might not be the words you use when thinking about your own body.

When we work together, I will always respect whatever language you prefer to use.

-

Having weight concerns and wanting to lose weight is COMPLETELY understandable - we live in society that idolises thinness, and have a healthcare system that medicalises fatness.

It is established in the research - dieting does not work long term for most, and dieting does harm.

The human body is hard wired against food restriction.

food restriction for intentional weight loss has a long-term failure rate. Most people regain the weight within 1-5 years. (Mann et al., 2007, Dansinger et al., 2007; Schmitz et al. 2007; Stahre et al. 2007; Cussler et al. 2008; Martin et al. 2008; Svetkey et al. 2008; Cooper et al. 2010; Neve et al. 2010, NHMRC 2013). Why? Complex biological factors defend against weight loss from millennia of evolution surviving famine. You have not failed, the diet failed you.

Food restriction for intentional weight control is lifelong (because of weight regain). It becomes a dreary path and can be a distraction from sustainable health behaviours. At worst it causes harm. See below.

2. Dieting is a risk factor for weight cycling, poor body image, emotional eating and eating disorders.

Intentional weight loss efforts brings us into conditional relationship with our body, or body mistrust, based on external measurements rather than internal wisdom.

For many there is a sense of shame, intense frustration or failure when our bodies tell us they don’t want to be controlled (biological hunger, cravings, food preoccupation, irritability, gut issues, loss of control eating), and we succumb. No amount of willpower overrides millenia of human hardwiring.

3. Dietary restriction to lose weight has physical side effects including impact on bone mineral density and loss of lean mass (or muscle), fatigue, irritability. Gut issues and nutritional deficiencies can happen with more extreme diets.

-

Intuitive eating is a weight-inclusive approach that centres…

unconditional permission to eat when hungry and what you fancy.

eating for physical rather than emotional reasons.

tuning into internal hunger and fullness cues.

Through the work we are cultivating curiosity about our inner experience, which gives us the space to respond to needs, our bodies, imperfections and all.

It is in this space of body respect that sustainable health-promoting behaviours can take root.

This approach is supported by scientific research showing physical and psychological health benefits.

-

While this approach doesn’t pursue weight loss as a goal of treatment, we hold space to explore your weight concerns. This is because of how people are treated in our society based on weight.

We live in a culture that idolises thinness and medicalises fatness. There is a negative impact of this weight based oppression on physical and emotional health for higher weight people (O’Hara et al 2021).

And so we begin to dismantle the cultural messages that are handed to us from a young age - from family, friends, school, medicine, wider society - that teach us to ignore our body, or to override our body, or to despise our body or that we must control our body.

In sessions we hold space to explore these messages and how they have woven into your own relationship with food, movement and body image.

We do this work at your pace and at a depth you feel comfortable with.

-

Diet culture is a system of beliefs, customs and behaviours in society that value weight and body size over physical and mental wellbeing. (O'Shea 2020).

Diet culture is EVERYWHERE. So much so, we take it for granted.

Diet culture is a lucrative global industry worth almost $200 billion in 2019 and is tipped to reach nearly $300 billion by 2027. It is an industry that makes its money on repeat business, as diets don’t work (see the Futility of Dieting).

-

Weight stigma is when negative attitudes are directed towards larger bodies. It is a is a common form of discrimination that we can experience within healthcare, on the street, in our relationships, in our homes, in education, through media.

Weight stigma is chronic social stress (Sutin et al 2015) and it impacts physical and mental health. It has been associated with a 60% increased mortality risk (controlling for BMI). It is associated with metabolic dysregulation and inflammation. It has profound negative effects on mental health. People who have experienced weight stigma are far more likely to have anxiety or mood disorders (controlling for BMI).

-

We easily absorb negative messages about weight and direct them against ourselves.

Feeling we do not measure up because of our body weight can rupture how we see ourselves in the world, our body image, our relationships, and how we relate to food and movement.

Researchers call this ‘Internalised Weight Bias’. It really impacts our physical and emotional health.

Emotional impact:

• Poor body image

• Disordered eating e.g. emotional eating or yoyo dieting

• Dieting for thinness

• Low mood, anxious mood

• Low self-esteem

• Reduced motivation to exercise

• Keeping friends and loved ones at a distance)

Physical impact:

• Raised blood fats

• Raised blood glucose

• Weight increase

• Metabolic syndrome

• Raised inflammatory markers

• Raised stress hormone

• Weight up and down

-

The traditional ‘biomedical’ model of healthcare is weight-focused. For higher weight individuals there are many aspects of health considered, but body weight control remains a key intervention.

Weight-inclusive care is different. It recognises that weight and weight loss are unhelpful focuses for long-term health and health enhancement (Levinson et al 2023).

Weight-inclusive approaches are linked with positive health outcomes.

The traditional biomedical model of healthcare recognises the harms of weight stigma. However it does not examine that pathologizing of higher body weight fuels weight stigma and diet culture.

Weight inclusive care rejects the medical pathologizing of higher weight bodies.

Research reporting population level mortality and morbidity outcomes against BMI typically fails to account for the cumulative impact of weight cycling, diet quality, physical activity levels, or the effects of weight stigma, discrimination and weight-based gatekeeping in healthcare. These variables are present but typically unacknowledged. (Fiona Willer Weight Neutral Training)

-

Calogero RM, Tylka TL, Mensinger JL, Meadows A & Daníelsdóttir S (2019) Recognizing the Fundamental Right to be Fat: A Weight-Inclusive Approach to Size Acceptance and Healing From Sizeism, Women & Therapy, 42:1-2, 22-44, DOI: 10.1080/02703149.2018.1524067

Cooper Z, Doll HA, Hawker DM et al. (2010) Testing a new cognitive behavioural treatment for obesity: A randomized controlled trial with three-year follow-up. Behav Res Ther 48(8): 706–13.

Cussler EC, Teixeira PJ, Going SB et al. (2008) Maintenance of weight loss in overweight middle aged women through the Internet. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16(5): 1052–60

Dansinger ML, Tatsioni A, Wong JB et al. (2007) Meta-analysis: the effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Ann Intern Med 147(1): 41–50.

Levinson, C. A., Fitterman-Harris, H., & Becker, C. (2023, September 10). The Unintentional Harms of Weight Management Treatment: Time for a Change. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SU6ZK

Mann, T., Tomiyama, A. J., Westling, E., Lew, A. M., Samuels, B., & Chatman, J. (2007). Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. The American psychologist, 62(3), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220

Martin PD, Dutton GR, Rhode PC et al. (2008) Weight loss maintenance following a primary care intervention for low-income minority women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16(11): 2462–67

Neve M, Morgan PJ, Jones PR et al. (2010) Effectiveness of web-based interventions in achieving weight loss and weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obesity Rev 11(4): 306–21.

NHMRC 2013 National Health and Medical Research Council - Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia. Melbourne: National Health and Medical Research Council

O'Hara, L., Ahmed, H., & Elashie, S. (2021). Evaluating the impact of a brief Health at Every Size®-informed health promotion activity on body positivity and internalized weight-based oppression. Body image, 37, 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.02.006

O’Shea, Laura. (2020). Diet culture and Instagram: A feminist exploration of perceptions and experiences among young women in the midwest of Ireland. Dearcadh: Graduate Journal of Gender, Globalisation and Rights, 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.13025/64p6-3p21

Orr, G; Kelly, T; Taylor-Beck, T; Rossiter, S; Badloe, N; Kostouros, A; Bast, A; Brassington, L; Willer, F. (2023). Towards Size Inclusive Health Promotion. Better Health Network. Melbourne.

Schmitz KH, Hannan PJ, Stovitz SD et al. (2007) Strength training and adiposity in premenopausal women: strong, healthy, and empowered study. Am J Clin Nutr 86(3): 566–72.

Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ et al. (2008) Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA 299(10): 1139–48

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., & Terracciano, A. (2015). Weight Discrimination and Risk of Mortality. Psychological science, 26(11), 1803–1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615601103

Tomiyama, A.J., Ahlstrom, B. and Mann, T. (2013), Long-term Effects of Dieting: Is Weight Loss Related to Health?. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7: 861-877. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12076